Before I jump in, I’ve got a few people to thank:

whose comment to me on writing about tough subjects, specifically “sometimes I think the only way out is through,” came exactly when I needed it this week. Thank you for offering kind encouragement; it helped. To whose courageous vulnerability is always an inspiration when treading into difficult territory. Her most recent post is so brave and honest. To for writing about the hardest things with such simplicity and compassion. And to all the poets participating in NaPoWriMo for being so gracious about my time on the sidelines while you’ve all written glorious poetry. It has been such a treat to read all your work.Hard things are hard to write about. (Duh, right?) When something is scary or sad it’s hard to look it right in the face. It’s even harder to turn it around and upside down and look at it from other angles. Which is what you have to do if you’re going to describe it, elucidate it, or otherwise capture it in words. It’s also what you have to do to simply process it and move on. But I don’t like looking at things that scare me. I’m easily spooked. I don’t watch horror movies. I cover my eyes during the tense moments in network TV, for heaven’s sake. I am afraid to talk about things that frighten me for fear the thing will hear its name and come closer.

I had a bit of a health scare over the last few weeks. My dermatologist found skin cancer on my cheek. It was Stage 0 which was very good news. It did require a procedure that took several days in order to remove it. Those days were bruising: the drive to the office, the needles, the excisions, the waiting until the next day to hear if we were done or if I’d have to do it all again. And the location, on my face, meant there was no hiding it, no keeping it to myself. I couldn’t pull on a long sleeve shirt and run out to the grocery with nobody the wiser.

I stayed home a lot, relied on my husband to do all the venturing out that was required. He also came with me to every procedure, asked all the questions I was too afraid or distracted to ask, cooked for me, held my hand, and took care of me through all of it. He has changed my bandage every day, except for the couple of days our son came home from college to see me. He is our resident medic with a calm, gentle skill and lack of squeamishness that made him the perfect candidate to peel off the bandage that first day after the stitches went in.

He got right up close to my face for a careful inspection and told me it looked amazing, the stitches impossibly tiny, the edges perfectly matched and flat. “You’ll barely have a scar, Mum,” he said, and pulled up his pant leg to show me the subtle white line from his knee reconstruction a few years ago. “Yours looks way better than this one did after surgery. It’s going to completely disappear.”

My daughter came home that weekend, too. She baked cookies and made me laugh and kept her brother’s imminent arrival secret until I heard the back door open and saw her grin. The best medicine in the world was the four of us around the dinner table and crashed on the couches in our regular spots watching a movie together. But it also showed me my real fear, the big one: the fear that something could change all of this, all of us.

The fear of loss, of death, mine or someone else’s, haunts me. I lost my dad at age 16. A year later was my aunt. A year after that was my uncle. The next year was my half brother. Those four years left me waiting constantly for the next bad news. Flinching away from what I was sure was just around the corner, not willing to look it in the eye. Kind of like the way I’m avoiding my face in the mirror these days.

But the cancer is gone, and my face will be fine. (I was chatting with friends at work about needing to make up a good story to explain the scar. “It should definitely involve pirates,” one of them said. You’ve gotta love librarians.) So now I’m working on the rest of it. The fear of it happening again. The knowledge of just how fast things can change. The realization that peace of mind is so easy to shatter but so very hard to piece back together.

A smart person I know with whom I was chatting about all of this said that when she’s going through something hard she always tries to ask herself, “What am I learning from this?” I’m not sure I know what the final lessons will be. I know they have something to do with fear, loss, and uncertainty. With living in the moment, and knowing the difference between vigilance and anxiety. There’s no poetry in this yet for me. But writing this introduction for you all to this week’s poem has made me take a longer look at what just happened and how I feel about it. Which is a good first step.

This week’s poem is one I wrote about a scary thing that happened to my son. As I said, I don’t like scary things, so I’m going to tell you right now that he’s fine. You don’t need to cover your eyes. It took at least a year after the event for me to even consider writing about it, until I could really look it full in the face. Then I looked backward to my college days, studying anthropology and archaeology, and thought about it from a different angle, from a vantage point that helped me experience a measure of comfort around a difficult experience.

Ancestor Worship

The day my son was hit by the car

I told him to be careful walking to school.

A seventeen year-old, he had been finding his way

around our small city on foot and by bike for years.

But that morning, as he slung his backpack over his shoulder,

I said it: “Be careful walking to school today.”

I hadn’t planned to say it, hadn’t seen it making it’s way to my lips,

but there it was: “Be careful walking to school today.”

He laughed at me, not unkindly, just the way seventeen year-olds

laugh at their mothers. “Mum, I’m walking, not biking.”

“But it’s snowy,” I said. “And people are stupid.”

Familial shorthand for a much longer warning

about distracted drivers. He lifted his chin and shrugged

his shoulders in a combined motion that said

both “fair enough” and “don’t worry.”

Later, when the call came, and after, I remembered

what I’d said and wondered how I had known.

What voice had whispered in my ear? Were there hands

that belonged to that voice? Had they softened his fall when,

struck hard, he left the ground? Had they eased the

landing that should have broken bones, but didn’t?

“That’s one tough kid you’ve got,” we heard again

and again. And he is. Young, and strong, and resilient.

But, still. “People just don’t tangle with SUVs and

come away with no breaks, no stitches,” the EMTs said.

And I thought again of the warning that came

from my mouth, but not from my mouth.

Standing around him in the ER, we made jokes,

the way you do when, having narrowly escaped

tragedy, the air tastes sweet. He started constructing

a physics problem to determine the speed with which he slid

across the pavement, livid red staining elbows, wrists, hips.

More burn than scrape. Nurses came and went, exclaiming

that he wasn’t more seriously hurt. “Lucky kid,” they said.

I imagined again those arms, reaching for him, softening

the impact, and recalled the ethnographies read in college.

There are cultures that venerate their ancestors as gods, and

I can see more clearly now why that might be wise.

Could some distant relation be watching us still? Maybe

the blacksmith, whose slender frame belied great strength,

is standing near. Or the farmer who pulled a man from the icy river

and once leapt to the backs of a runaway team of horses.

Such heroics in life could still echo after death, I think. Or the mother

who crossed an ocean with her children, giving birth at sea and

carrying that daughter safely to a new home. She would not

easily forget the value of a child.

What offering might I make by way of thanks to these shades?

A cup of wine, a candle lit seem paltry reward for their service.

Perhaps it simply is the way of things, and they would not know

or thank me for my acknowledgment. And maybe one day, if I am right,

it will be my lips that sigh into another mother’s ear, and my body

that cradles a boy who should not meet the roadway

without a mother’s arms beneath his head.

Thank you all for being here. As Noha said, the only way out is through. But you don’t have to travel alone. Which brings me to my little public service announcement: Friends, get your spots checked. You’re not all as pale and freckled as this mostly-Irish American. But if it’s new, or weird, or different than it was, see a doctor. Advances in treatment are miraculous, but so much relies on early detection. Take care of yourselves and don’t wait.

What I’m Reading:

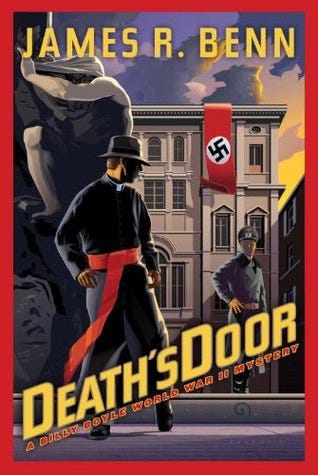

Comfort reading has been utterly necessary the last few weeks. For me that means mystery novels. I know. I just got done telling you I don’t like scary things. But mysteries are different somehow. For me there is no better distraction than a great mystery series and that feeling of meeting up with a bunch of old friends and watching them puzzle out the solution to a crime. I read And Justice There is None, by Deborah Crombie, number eight in the Kinkaid & Jones series. I was about to start on a “better” book this week. You know, something “literary” that’s been nominated for awards. But I paged through it and saw it headed in a pretty dark direction. I’m just not really in the market for apocalyptic right now. So I took my husband’s advice and picked up the book he just finished, the seventh novel in the Billy Boyle series by James Benn, Death’s Door. Behind enemy lines in Italy, World War II, an Irish American cop from Southie trying to complete his mission and rescue the love of his life at the same time. Yeah, that’ll do just fine.

Thank you all for reading. Have a great weekend.

So glad you are on the mend, Tara. 🩷 And that you got good news about the results. And such beautiful comfort to be embraced by the ones we love when we are scared. Hooray for your lovely family. Your poem is beautiful. (The last few lines are so touching my eyes misted.) The parallels between being held by the ancestors in your poem and you being held by your family are so powerful. Held through time, by the living and the dead. (And thanks for the PSA. It's a good reminder.)

One of the things I read when I had cancer (so long ago) is that it’s like this: in life, you get up every morning and don’t expect to be hit by a car. But then one day you are hit by a car and you get up forever after worried you’ll be hit again. It’s true - to an extent. It changes you. But I would add that today I don’t normally have those worries; I fact, I enjoy so much of life. I’m so glad you’ve come through this, Tara. I wish you many, many days, months and years of happiness ahead.