What a week! Taxes (our own and my mother’s) and a time consuming issue with my mom’s memory care facility have eaten up every spare minute. It’s weeks like this that break the rhythm of writing for me. It’s all well and good to say I’m going to prioritize writing but when you’re a parent, a daughter of a dementia patient, a human who must file taxes, and a librarian, sometimes it’s just not an option. And when one busy week leads directly into another, suddenly you’ve lost the thread entirely, gotten rusty. That tap that seemed to flow each time I sat down to write has gradually slowed to a trickle. I’ve been so grateful for

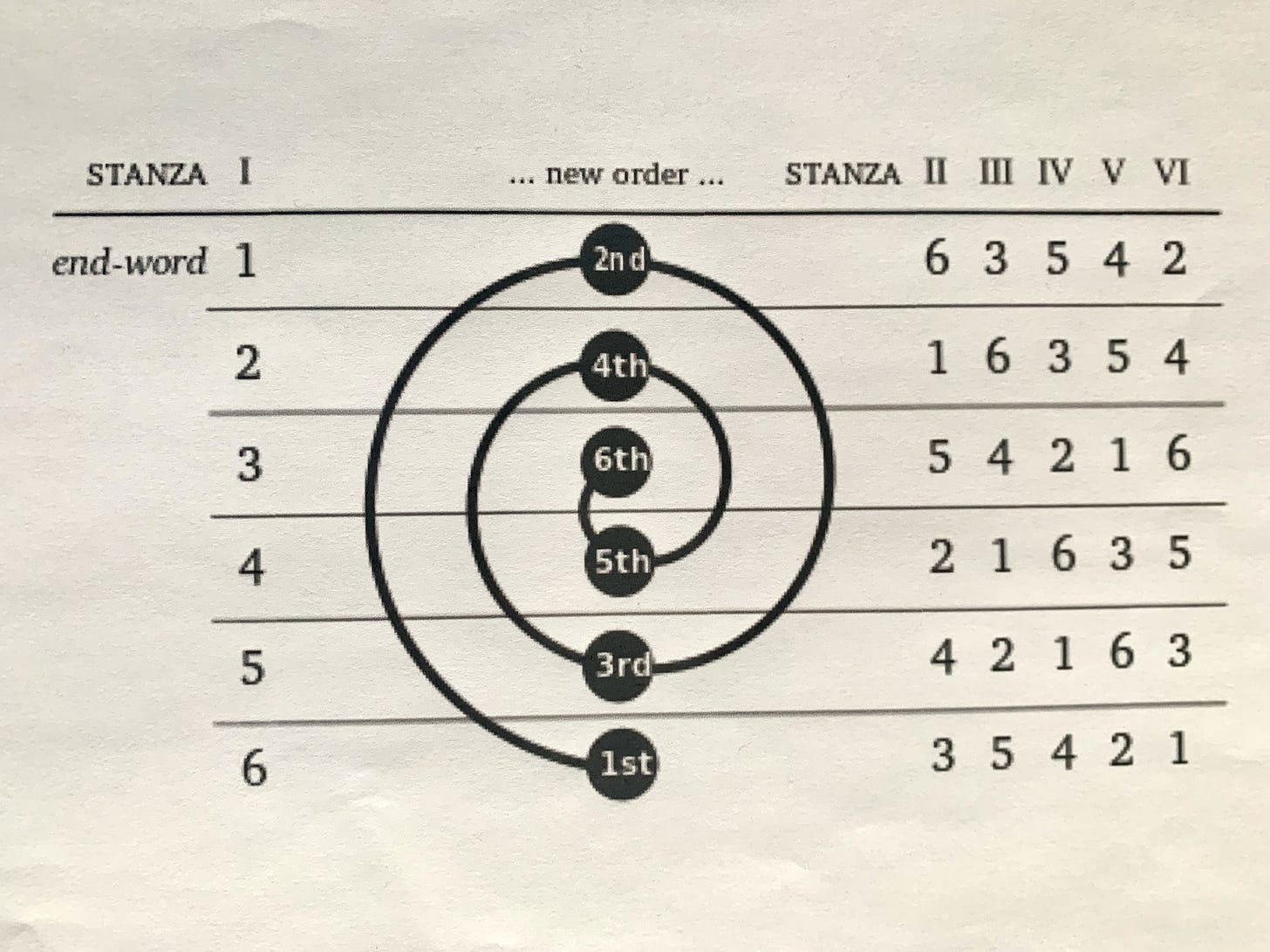

’s February Poetry Adventure this month, but I’ve missed too many days this week and responding to the prompts is getting harder.What’s a poet to do when the well feels dry? I’m so glad you asked! If you’ve been here a while you know my fondness for closed poetic forms. Concretes and villanelles and pantoums! Oh my! Sometimes a bit of structure is just what I need to get back on track. And when it comes to closed poetic forms I think there’s no challenge greater than the sestina. It’s composed of an intricate series of repeated endlines over the course of six stanzas, followed by an envoi, which is a final three line stanza that incorporates all six repeated words. A sestina repeats the ending words of each line in the first stanza in a different order in each following stanza.

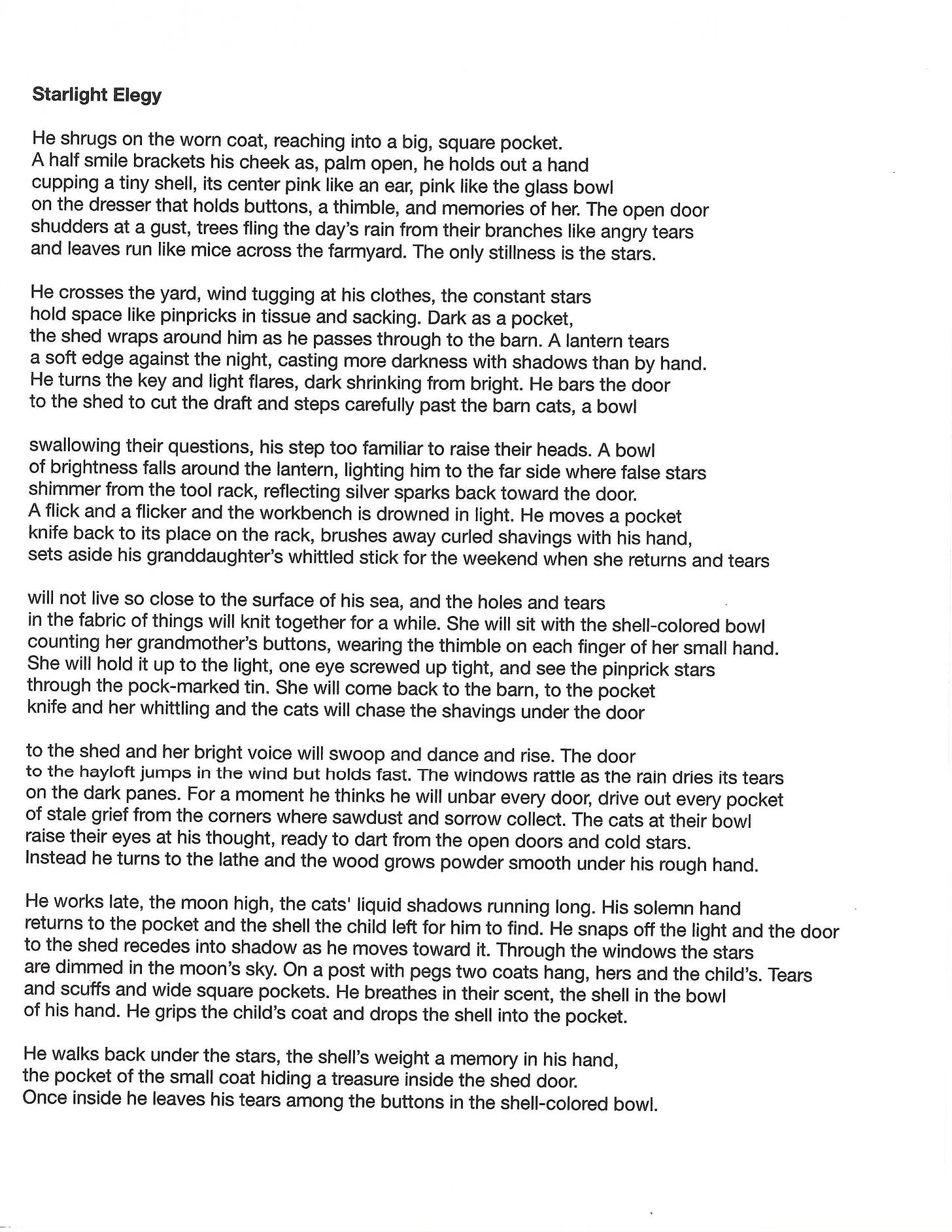

I’ve only ever written one sestina which I’ll share with you below. I’m very fond of it, despite the fact that my fondness has not been shared by a single lit magazine editor to date. It has a narrative which grew very organically from the form. It’s not based on anything from my life, except that the barn and wood shop are what I imagine my grandfather’s might have looked like, and we do have a silly game with our daughter that’s been going on for years now in which we hide a key chain in each other’s coat pockets.

For me, the trickiest thing about tackling something like a sestina is getting started. I began writing the poem below by arbitrarily picking six words to use as the end words. I chose pocket, hand, bowl, door, tears, and stars. You’ll notice that they are not particularly fancy words. You need to be able to recycle these same six words through six stanzas, so byzantine and conundrum might sound fun but versatile they are not. Also I found it helpful that the word tears has two entirely different meanings and pronunciations. One of the few times I cheered that particular peculiarity of the the English language. It really gave me seven words to work with instead of six. Clever, no?

Then I followed the diagram in the photo above and typed out my end words in that order. I then wrote up to each end word. It was challenging, but the structure and framework with which I started made it easier than if I’d just winged it.

Why am I telling you all of this? Funny you should ask. I was thinking, as a way to light some poetic fire, I might attempt a sestina this next week. And I was also thinking that maybe you would like to try one, too. You could choose your own end words or borrow the ones I used below if you like. We could meet back here in, say, two or three week’s time and compare notes, or more accurately, complex poetic forms.

You needn’t write a poem with such a clear narrative as mine. And your lines do not need to be as long as mine. It’s actually easier if they are not since long lines want to wrap on the page and ideally you want those end words not to wrap to the next line. I like to tell myself that my poem was rejected so thoroughly because it would have been hard to reproduce in a clear fashion. What? It’s possible. Because of the length of the lines, I’m including the poem here as an image to preserve the formatting. I hope it’s legible for you.

If you’d like to read another sestina before you attempt your own you could try Sestina, by Elizabeth Bishop. You could also start out with a sestina and then pitch the structure out the window if the poem that emerges doesn’t want to conform. There are plenty of poems out there that are considered sestinas but that bend the original rules into some pretty interesting shapes, like The Weary Blues, by Langston Hughes. Rules are made to be broken, right?

No further reading recommendations for you today. I had no time to read much of anything this week other than infuriating emails and tax instructions. I cannot, in good conscience, recommend either of those to you.

Thanks for being here.

Brava! Beautiful and memorable.

I’m also a fan of closed forms, though I find them very difficult. The result can be so surprising. I’m hoping to try one with you.

My first experience reading a sestina (to my knowledge). Imagery for days, and the attention to detail - just beautiful. Appreciate the starter tips and diagram as well. Thank you for sharing and for sparking interest in a new-to-me format, after tackling a villanelle recently this brings new perspective. I’ll be thinking of this Starlight Elegy for a good bit of time! Looking forward to your new sestina.